[1] In Despeux, Catherine. 1989. Gymnastics: The Ancient Tradition. In Kohn 1989.

[2] See: http://literati-tradition.com/qi_gong_origins.html

[3] Liu, T, ed. 2010. Chinese Medical Qigong. Singing Dragon, London

[4] Roth, H. D, Original Tao: Inward Training and the Foundations of Taoist Mysticism. Columbia University Press: New York. p76.

[5] Harper, D, 1998. Early Chinese Medical Manuscripts: The Mawangdui Medical Manuscripts. Wellcome Asian Medical Monographs: London.

[6] Graham, A. C. 1986. Chuang-tzu: The Inner Chapters. Allen and Unwin: London. p265.

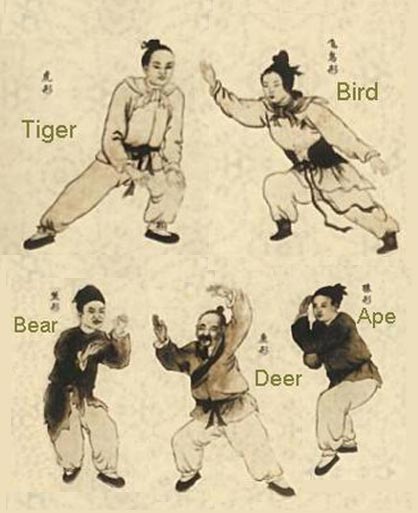

[7] This is repeated, more or less in, “Therefore, the authentic men in their roamings do not let their hearts be disturbed by puffing and blowing, inhaling and exhaling, expelling the old, taking in the new; bear lumbering, bird stretching, duck ablutions, monkey jumping, owl gazing and tiger staring – all that is for men to nourish the body.” Bromley, M et al, 2010. Jing Shen: A Translation of Huainanzi Chapter 7. Monkey Press.

[8] From Zhuangzi chapter 11, Zai You (Letting Things Be), translation from Liu, 2010, p39.

[9] Of course even ‘active’ practices (as compared to what Kongzi/Confucius called ‘mind fasting’ or ‘sitting and forgetting’) can be very internal and quiet and there are a host of techniques where the body is held still in standing, seated or lying meditation while one uses visualisations, special breathing methods such as inhaling sun or moon essence, and mental direction of qi flow to different regions of the body.

[10] As a general rule, quiet and still practice is considered to be more nourishing and more conducive to mental and spiritual development, while active practice is more moving and strengthening. But as the yin and yang of practice they inevitably overlap.

[11] Legendary Emperor, traditionally dated 2356-2255 BCE.

[12] Despeux, Catherine. 1989. Gymnastics: The Ancient Tradition. In Kohn 1989. p238.

[13] Knoblock, J, Riegel, J, 2000. The Annals of Lü Buwei: A Complete Translation and Study. Stanford University Press.

[14] Quoted in Kohn, L, 2005. Health and Long Life: The Chinese Way. Three Pines Press: St. Petersburg. p12.

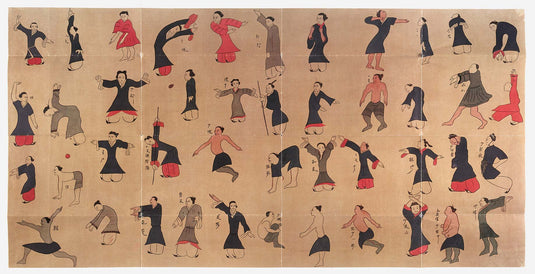

[15] A poster of the restored scroll can be obtained from https://www.jcm.co.uk/mawangdui-poster.html

[16] Kohn, L (2008). Chinese Healing Exercises: The Tradition of Daoyin. University of Hawai’i Press, Honolulu, HI, p49.

[17] In Stanley-Baker, M (2006). “Cultivating body, cultivating self : a critical translation and history of the Tang dynasty Yangxing yanming lu (records of cultivating nature and extending life)”. Indiana University MA thesis.

[18] Mafeisan – a preparation thought to have included cannabis and datura.

[19] Different five animal traditions relate the animals to other organs.

[20] The Yangsheng Yaoji (Essentials of Nourishing Life) by Zhang Zhan now only survives in fragments and mentions in other texts.

[21] Taiqing daoyin yangsheng jing (Great Clarity Scripture on Healing Exercises and Nourishing Life) quoted in Kohn, L (2008). Chinese Healing Exercises: The Tradition of Daoyin. University of Hawai’i Press, Honolulu, HI, p100.

[22] Despeux, C (1989). Gymnastics: The Ancient Tradition. In Kohn, L (1989). Taoist Meditation and Longevity Techniques, Centre for Chinese Studies Publications, Ann Arbor, MI, p239.

[23] Sun Simiao, On Preserving Life (Baosheng ming) in Kohn, L (2008). Chinese Healing Exercises: The Tradition of Daoyin. University of Hawai’i Press, Honolulu, HI, p134.

[24] Wilms S (2010). “Nurturing Life in Classical Chinese Medicine: Sun Simiao on Healing without Drugs, Transforming Bodies and Cultivating Life”, The Journal of Chinese Medicine, vol 93, p13.

[25] The combination of seasonal solar changes with the twelve lunar months gives 24 two-week periods essential for the agricultural rhythm of the year. Kohn, L (2008). Chinese Healing Exercises: The Tradition of Daoyin. University of Hawai’i Press, Honolulu, HI, p170.

[26] Tianjun Liu and Xiao Mei Qiang (Editors) (2010). Chinese Medical Qigong. Singing Dragon, London, p54.

[27] A traditional martial practice designed to strengthen the body so that it can withstand blows. Some hard qigong practices can be seen at the popular Shaolin monk shows, for example bending spears with the throat or having paving slabs broken over one’s head.

[28] Possibly his uncle, 5th successor of the Neiyanggong lineage.

[29] “My organs move, my mind is still”.

[30] “A Brief History of Qigong”, Journal of Chinese Medicine, 105/5. Available: https://www.jcm.co.uk/a-brief-history-of-qigong.html