I spent part of lockdown writing a new book, with all profits going to the Chinese Medicine Forestry Trust. It’s a raw and honest account of childhood, teen rebellion, drugs and hippie travelling, transformation into a natural foods pioneer, studying Chinese medicine and more.

It’s available as an e-book from Amazon (you don’t need a Kindle device – you can download a free app for phones, tablets, laptops etc.). Apologies for using Amazon but it’s realistically the best option, with for authors and readers – I guess that’s why they are so successful.

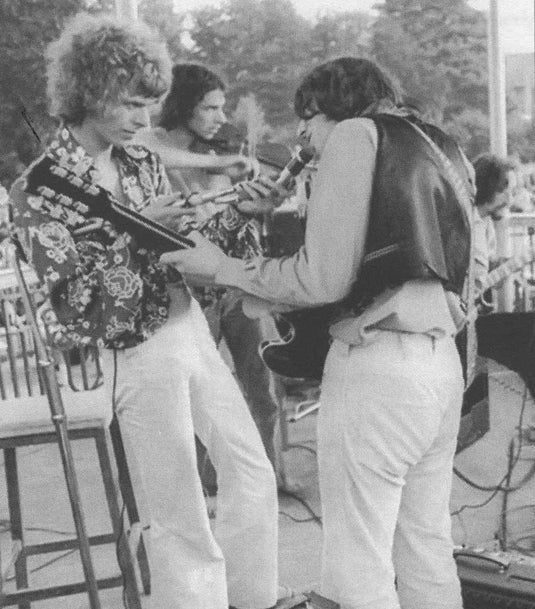

Here is a sample from Chapter14: Music

When I was twenty-one, David Bowie (on the cusp of fame) and his girlfriend Mary Finnigan opened the Beckenham Arts Lab in the Three Tuns pub. It was the nearest thing to my local since I’d spent many hours there, mingling with my anarchist and CND friends. And somehow, Mick (guitar), Bob (drums), my brother Alan (harmonica) and I became the Art Club’s house band (going under the dreadful name of Oswald K. Aldehyde). Lacking a trace of self-doubt, we’d launch into blues or jazz covers – Miles Davis’s So What was a favourite – which rapidly degenerated into long and self-indulgent noodlings.

I didn’t take to David Bowie in those early days. Always a chameleon, this particular incarnation was full of a luvvie campness that couldn’t have been further from the worthy authenticity of my black and white politics. As soon as he’d announced us he would disappear into a back room. I had no complaints there – I wouldn’t have stayed to listen to us either – but when he swanned back at the end of our set saying how absolutely faaaabulous we were darlings, I choked on the insincerity.

When he died in 2019 I spoke to my brother about those times and he told me something I have no memory of.

“We were at Brian Eno’s house,” he said, “and you had a row with David about how he shouldn’t be charging people money to get into the Arts lab. You kept calling him a ‘bread head, man’ “ [bread head = money-obsessed in hippie talk).

The summer of that Arts Lab year, 1969, Bowie organised Britain’s first Free Festival in our local park. Beckenham Recreation Ground represented everything I’d loathed about growing up in this bland London suburb. Grass cropped to within an inch of its life, dogshit, mean little flower displays, thorny, clipped bushes spaced out along bare and barren beds, a sour and officious park keeper and bored kids hanging out by the swings, smoking, and wondering what terrible fate had condemned them to live in Beckenham. This was the park where I’d walked our dog Rex as a kid, wondering when the hell my life was going to begin.

But this day it was transformed. A crowd of hippies lounged on the grass and the smells of weed and patchouli wafted through the park. We’d put together a scratch band with a guest drummer, managed a quick soundcheck, and halfway through the afternoon launched into our first number. Within seconds Mick – our front man and the only real musician in the band – started turning his head and looking back at us with an agonised expression. It wasn’t till the end of the song we saw he’d busted two strings. We soldiered on with our next tune but had to abort the gig halfway through when the park-keeper – in full uniform and shiny peaked cap – wrestled our drummer to the ground, kicking the drums away and screaming “You’re not playing that bloody loud in my park”.

On the 50th birthday of the festival, after Bowie had recently died, the bandstand was given Grade 2 listing as a historical monument and a photo appeared in most newspapers and TV channels. There I was with my violin, somewhere to the rear of a supremely cool-looking Bowie, while Mick sat plucking at his guitar strings.