A few years ago I trekked from one side of Kyoto to the other to see an exhibition of precious Japanese tea vessels – lent by various eminent scholars and abbots. I was expecting to see the kind of delicate porcelain cups that I reglarly visit in the British Museum’s wonderful Chinese ceramics rooms. Instead I was confronted by cases full of what (to my ignorant eyes) looked like the kind of thing five year olds bring back from their first clay class.

It led me to think about the discussion of carved versus uncarved blocks in Chinese Confucian and Daoist philosophies.

Confucius compared our original human nature to an uncarved block (of wood or stone), waiting to be shaped and refined through self-cultivation, for example by leading a moral life, practising ritual, studying, embracing honest self-reflection and so on. In the modern world, we might aspire to carve our block through the practice of meditation, yoga, qigong, psychotherapy, a healthy diet, exercise and more. We might think of ourselves as a work in progress, and even when we know there is no pot of gold at the end of the rainbow, no first prize waiting at the finishing line, we may still hold the idea of continuous progression.

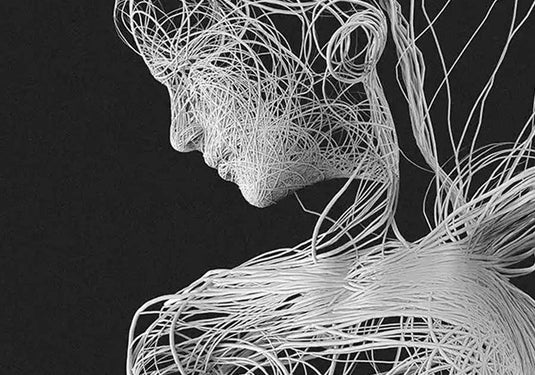

Daoism, by contrast, wholeheartedly embraces the uncarved block (‘pu’ = unworked wood, inherent quality, simple, natural state). One of China’s earliest doctor-philosophers was Ge Hong (3rd/4thcenturies). In his book Master who Embraces Simplicity, he wrote. “Evince the plainness of undyed silk, embrace the simplicity of the unhewn log; lessen selfishness, diminish desires; abolish learning and you will be without worries.”

This ties in with the Daoist concept of ‘ziran’ (difficult to translate but often rendered as ‘self-so’). Natural forms in their infinite variety (think snowflakes) pour forth from nothingness/emptiness/the Dao. Trees, plants, rocks, animals, insects are all ziran. But most human constructions are carved blocks – skyscrapers, roads, cars (although as time, weather and entropy act on them they steadily become more ziran). And we humans, of course are also ziran which is why we respond so deeply to natural and weathered forms.

One activity where these two approaches (the carved and the uncarved) can be explored is meditation. Some practices shape the mind through visualisation, counting the breath, paying minute attention to the body, repeating specific phrases etc. Others go in the opposite direction and practise what is called ‘zazen’ = just sitting in the Zen tradition, or what the Daoists call ‘sitting and forgetting’. This is undirected meditation, simply watching the natural rise and fall of sensations and emotions without attachment or attempts at controlling them. This doesn’t help us reach a destination so much as allow us to let go of the idea of having one.

So how does all this highfalutin’ philosophy apply to our daily lives? Personally I try to find a place for both the carved and uncarved.

When I used to play the violin I had to first approach it in a structured way, practising scales and exercises over and over to carve brain and muscle memory. But the best moments were when spontanaeity took over. As a Japanese saying goes, ‘first I will learn something, then the inspiration will come’.

It’s the same when I cook a dinner for friends or host a party or give a lecture. I prepare like mad (‘fail to prepare = prepare to fail’). Then at the right moment (as I welcome my guests or begin to speak), I have to let go and allow the uncarved block of spontanaeity to take over. I have talked to many friends, especially performers, who share this same experience. One told me that in the Greek theatre, the actors would put on masks to help them lose their personal ego identity, and then allow ‘the god to enter in’.

At other times, for example creative writing, the uncarved comes first, seeming to pour forth and leave us wondering where it came from. But inevitably that is followed by cutting, and carving it into shape.