A new slant on why exercising and moving are so good for us...

New Scientist, June 15th, ran an article by Herman Pontzer called ‘Step on it’, subtitled ‘We know exercise is good for us. But how much do we need?’

He points out that most animals are really lazy – resting and sleeping whenever possible to save energy for survival and reproduction. Great apes, for example, rest or sleep 18 hours a day.

But as our ancestors began hunting and gathering around 2.5 million years ago, they gained an evolutionary advantage from being able to exert themselves physically for long periods of time. Those who hunted or gathered more successfully survived better than others and passed this desire and ability to move onto their offspring. In return, evolution rewarded us by producing feelgood chemicals such as endorphins and endocannabinoids in response to physical exertion.

Pontzer suggests that in the millennia that followed, we successfully balanced these two opposing tendencies – our inherent laziness and the necessity of moving for many hours a day in pursuit of food and other necessities.

In the last century or so, however, most of us no longer need to exert anything but the minimum effort to obtain food and other essentials, and our innate laziness has taken over.

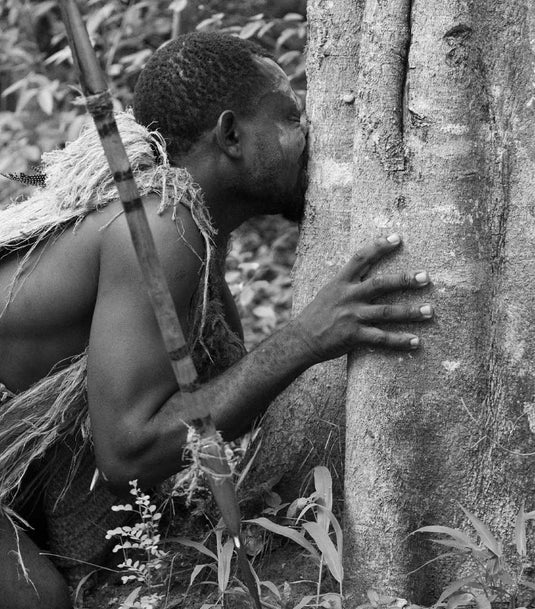

So far so unsurprising maybe. But then he said something that really hit me. His research on the Hadza hunter-gatherers in Tanzania revealed that they burn the same number of calories a day as adults living in the US and Europe, despite being five to ten times more active. And it wasn’t that they managed to use fewer calories when they exercised.

This might seem like bad news for people who hope they can burn off excess weight by exercising, but it reveals something really interesting.

The answer offered by Pontzner and his colleagues to this apparent paradox is that the Hadza used fewer calories in other aspects of their daily life.

By contrast, a sedentary person consuming large numbers of calories that are unused in physical exertion, is likely to burn the excess via harmful physiological responses such as inflammation and the fight-or-flight sympathetic nervous system response.

Both inflammation and sympathetic dominance (characterised by always being ‘on’, and feeling more stressed, wired, tense, fearful etc.) are linked to the development of most of the degenerative diseases we suffer from … cancer, heart disease, strokes, dementia, diabetes etc., which are virtually unknown among the Hadza.

These observations can help explain the findings across most animal species studied to date, that eating less is associated with more successful aging and a reduction in chronic disease. Maybe now, though, we can more correctly say that both eating less and eating normally while exercising much more will have the same beneficial effects.